The Fine Art of Sighing by Bernard Cooper Full Text

Many people observe themselves distracted by the current political climate, including writer-critic Bernard Cooper. "It's been the weirdest political year of my life," Cooper told me. "And I'grand an elderly person."

In a way we were meant to be talking nearly the span of Cooper'due south career, since we were discussing his experience with art, which, as he writes in his latest book My Avant-Garde Education, began when he came across a magazine characteristic on Pop Art in middle school. But we'd gotten off on a political tangent via Cooper's recounting of a operation he'd seen with some friends the night before. He described it every bit a long show with simultaneously spoken and sung narratives, which was so underwhelming that afterward 1 of Cooper'southward friends admitted that he "kind of wished we'd stayed abode and watched reruns of Gunsmoke instead."

"It had very little spontaneity, very trivial surprise," explained Cooper, who for many years was the fine art critic for Los Angeles Magazine. "Information technology checked all the boxes of the problems many artists feel obligated to deal with today."

He went on to clarify that information technology was the "obligated" part, rather than the issues themselves, that made the experience so lukewarm. The performance was "dead serious" and the audition was a "sea of stony faces." No wonder—the issue-heavy operation was nada they hadn't seen earlier. Experimentation is part of what defines performance art, just this show was near conservative in its predictability.

"Maybe this ballot does relate to our discussion in that mode," Cooper mused. "Trump is bandage every bit the radical and Hillary equally the conservative. Those words ain't what they used to be."

***

Cooper knows from conservative. He grew upwardly in the suburbs of Los Angeles, where his father practiced law and his mother stayed home and kept house—including a perpetually over-stuffed pantry—for her husband and iii sons. This all-American fifties lifestyle was a mark of particular success for his parents, both children of Jewish immigrants, but information technology wasn't without its heartaches: their eldest son, Bob, died of Hodgkin'southward disease when Cooper was a boy, and he spent many hours of his childhood lolling on the couch across from a portrait that his blood brother Ron—also older, so much and then that he was already practicing police force by this time—had painted of Bob. On ane such lazy afternoon, Cooper discovered that what had appeared at a altitude to be a tie stripe was actually a line of text: Oh Bob, information technology read, Poor Bob.

"I realized that this awkward, amateur painting I knew so well independent something moving, and about frightening," Cooper told me. "This was my first inkling of the thought that art could embody these things."

Bernard Cooper

Cooper was already interested in art, especially Pop Fine art, which had thrown his young mind for a loop by introducing the idea that even ordinary pantry items could accept pregnant. But the act of discovering something new in his own brother'south painting, a painting he thought he knew so well, prompted him to brainstorm looking at art in a new way, searching each piece for hidden meanings or coded messages. This manner of looking came naturally, which he at present believes was a side event of his allure to men, which he felt from a young age merely kept hidden until afterwards college. Fifty-fifty closeted, he had an understanding that—especially in the highly charged atmosphere of the pre-Stonewall sixties—he had to always exist on the lookout for possible threats or allies. "You get used to looking at the globe in this closely observed manner," he explained, "constantly decoding for your own safety." It wasn't a especially fun way to grow up, he added, but information technology was "the perfect circumstances for a burgeoning creative person."

He wasn't simply speaking for himself. Since those isolated suburban days, he'southward met many artists, colleagues, and students, "whose origins are actually not conducive to becoming an creative person: mayhap they come up out of backgrounds where the family doesn't value art, or where financial needs always come first. They come out of it and make the art they need to make."

The give-and-take demand came up time and time over again every bit we spoke about this, and was perhaps best illustrated through the life of a playwright friend of Cooper'south, a gay human raised in a strict Baptist family who encouraged him to "get right with God" and marry a woman. Rebelling was emotionally very difficult, and for a long time he didn't—he even attended Oral Roberts University, a highly conservative Christian school where practicing homosexuality is even so, in 2016, confronting the honor code that all students are required to sign. But, gradually, "writing about gay subjects helped him extract himself from that earth," explained Cooper.

Maybe I'd been reading as well much news, but I kept picturing this playwright as an emigrant desperate to escape an oppressive regime, and his art equally the raft he built to take him to a safer identify. He was similar one of the avant-garde Soviet artists that New Yorker writer Andrew Solomon interviewed for The Irony Belfry: they were hassled or imprisoned by the KGB, simply their work was eventually discovered by the Western art marketplace, and this allowed some of them to travel outside of the UsaDue south.R. and feel things like intellectual freedom and fully-stocked art supply stores for the first fourth dimension. The experience was life irresolute, merely not wholly positive. As Cooper said, growing up in the closet wasn't great, but information technology did help make him an artist. Similarly, the Soviets had become artists as a way to deal with their oppression, and when that oppression was lifted some of them weren't sure what to make anymore. "To create richness out of plenty is worse than useless," Solomon writes of this sudden absence of inspiration, "it is wearisome."

The strange flip side of making art from oppression is that it means being dependent on difficulty in order to create. Some artists have made work about this very problem—Cooper gave me the example of a Raymond Carver poem chosen "Your Dog Dies," about finding out that the family unit dog has died and immediately thinking: how can I use this grief in my piece of work?

"There's something mercenary near it," concluded Cooper, "only it too does something that I think is miraculous: if you tin can take the unbearable or difficult or deeply unfair, those things in life that cause bully suffering, and stand back and figure out how to redirect them into a work of art that will allow other people to understand, that's a redeeming quality."

***

The experience of other people, i.e. art audiences, is an large part of Cooper'south chat: past coming into contact with art, he says, the viewer might detect that something familiar is "made fresh again," that their knowledge of the world is "sharpened," or they might, as in the case of the issue-heavy performance he'd just attended, feel like they're "in an endurance test." His descriptions come from both his experiences viewing art and from the experiences of others, which he'southward had a chance to observe over the course of his many years in the art world.

He got his first glimpse of said world in high school, when he scored a summertime job at a Los Angeles gallery. He wanted desperately to be role of the fine art world, where he felt he might really vest, but was underwhelmed by this preview: he'd pictured galleries equally pulsing with frenetic crowds driven by the aforementioned degree of passion that art stirred within him, but all he constitute were snooty staffers in otherwise empty spaces. His previous understanding of art had been importantly private, gleaned from magazines and books, and at present he had to face a troubling question: "Could the commerce of art really exist as impenetrable and lonely as information technology seemed?"

Many people might have given up on the art globe right then and in that location. The pristine spaces where art is traditionally shown can be daunting, every bit can the people in them, especially if they're dropping names of old masters and concepts and being deadly serious about the whole endeavor. "I would no more desire to exist in a room with someone who thought everything they said was meaningful and serious than I'd want to become to a performance where the creative person idea the same affair," Cooper told me. "It'southward express, and information technology'due south pretentious."

Both are critiques often given to the art globe at large, and they're not altogether false. I spoke to Derek Conrad Murray, currently Associate Professor of History of Art and Visual Civilization at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and writer of Queering Mail service-Black Art: Artists Transforming African-American Identity After Civil Rights, about his experiences in this scene, and he didn't hesitate to confirm that the institutions where art is often exhibited or discussed "are elite spaces, which has e'er been problematic." The problem is that this exclusivity can make the barrier to entry can seem impossibly high, keeping away potential art lovers and artists alike—including people who might really need the life raft of art. "On the other hand," Murray added, "people access art on multiple levels, and there are various forms of fine art making that are not best-selling as such past the highbrow value systems of the art world." This introduces another problem, he explained, in that the separation of different forms of fine art into high versus depression culture often reflects our culture'south ideas of who "deserves" to be called an artist.

Having learned his dearest of art from the relatively lowbrow Pop Art motion—full of glory, comic book, and suburban kitsch imagery—Cooper was possibly more able and willing than others to stick it out with art despite the bleak kickoff impression. In 1969, nevertheless on the hunt for an art community to phone call his own, he applied to the then-fledgling Cal Arts and found himself suddenly immersed in the avant-garde. His swain students were art obsessives just like him, and they spent their days busily typing words over other words or saving locks of their ain hair, supervised by a roster of professors that included conceptual artist John Baldessari, whose famous works include The Artist Hit Diverse Objects with a Golf Club.

These projects might audio similar just more art-speak today, only at that time the avant-garde was withal considered truly avant-garde—new, weird, and controversial—and many people did not accept information technology as art. This was intentional; the aim of avant-garde artists was not to achieve inclusion in the art globe as it was, merely to subvert its norms. Some had more difficulty than others finding acceptance due to their race or sex activity, like Korean American Nam June Paik, the father of video art, or Judy Chicago, pioneering feminist artist (both, incidentally, taught at Cal Arts). The only way for them to get into the fine art earth was to remake it.

This outsider status wouldn't last long. Fifty-fifty as Cooper was watching his friends perform conceptual pieces in the old girls' high schoolhouse that served equally their campus that first year, the art earth was in the process of accepting and subsuming the sixties avant-garde. In 1966, for example, artist Ed Ruscha painted The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire to illustrate "an uproarious period in which artists felt increasingly alienated from cultural institutions," according to MoMA's description; iv years after, Ruscha represented the U.s. at the Venice Biennale, a venerable art world institution. According to Cooper, the Biennale had begun exhibiting such a variety of avant-garde art that it even inspired a Cal Arts rumor that a man had been sighting running away from the Biennale screaming, "In that location's too much art! There'due south too much art!" before eventually projectile vomiting into a canal.

It was enough to make Cooper wonder, while however reveling in the shared passion of his new industrious community: "Had the cutting border grown dull at final?"

***

At that signal Cooper was notwithstanding years out from becoming a critic, but he was already thinking like 1, preoccupied not but with how to brand art but also why and for whom. One day at CalArts, for example, he was distracted from a classmate's performance—the pupil was beating his knees to the sound of static—by the blasé attitude of the schoolhouse secretarial assistant who popped her head in midway to deliver a bulletin. Cooper explained to me that one of his standards for what makes a piece of art good is that information technology "throws you at some point." The secretary wasn't thrown at all; she'd gotten used to seeing new, weird, and controversial things. Cooper realized that newness wasn't enough to really throw a viewer; even the well-nigh up-to-the-minute artwork might be revealed equally meaningless at its core.

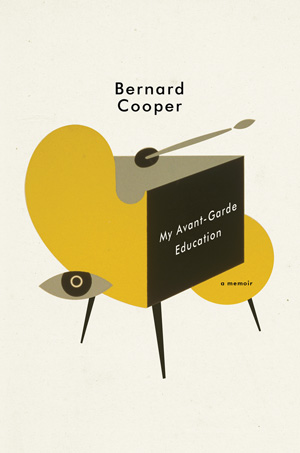

My Avant-garde Education: A Memoir

by Bernard Cooper

(Westward.W. Norton, February. 2015)

He has been thrown by cut-edge pieces and more than conventional piece of work alike, from the provocative photos of Robert Mapplethorpe to the traditionally structured stories of Alice Munro. Whether or non a piece of art is avant-garde, he explained, has no begetting on "its ability to brand you gasp"—though he notwithstanding holds a spot in his heart for the avant-garde as a motility. "It was where I got started," he explained. "I still love new art."

This zipper may cause him to be extra hard on art that makes false claims on the avant-garde. My Avant-garde Education includes Cooper'due south thoughts on an exhibit that included real human body parts. This wasn't a new thought—Baldessari really attempted something very similar in 1970—and it wasn't thought provoking either, unless you count Cooper'southward thought that it might be "a course of condescension to call up your audition is so literal" that they could only recall about mortality in the presence of dead bodies. Cooper, who has lost all his immediate family unit and his long-term partner, plus many friends in the AIDS crisis, was in no demand of whatever kind of mortality wake-up call to begin with, much less a heavy-handed one. His critique is blistering: "I'd rather be turned into fertilizer than donate my carcass to art," he writes. "I know how astonishing and fine a matter it tin exist, and I also know what ugly junk can be made in its name."

Such gruff statements stem from a state of being he describes as "a muddle of half thoughts and contradictory emotions" that makes him "pathetically grateful" for fine art that jolts him—and ornery towards art that doesn't. He refers to this as "my crankiness," and there'due south a certain down-to-world amuse to it, like when he complained to me that a show he'd seen recently was not only predictable, it also required the audition to sit on the footing. "If I'm going to sit on a cement floor," he grumbled, "I'd similar to be surprised." So he laughed.

This exchange was typical of my chat with Cooper, and of his writing, which inclines toward the self-deprecating and has the tendency to go funnier as it gets darker. He is perhaps at his funniest when writing almost his father'southward dementia and death in his 2007 book The Bill From My Begetter. "If something is too grim I starting time to see things that are funny, and vice versa," he explained. This addiction gives his books an affable, generous experience—it never seems every bit if he's preaching—and also helps explain his impatience with too-serious art.

"Art that is admittedly serious doesn't take doubt into account," he explained. "The artists that I like always have a petty insecurity about what they're doing." Self-skepticism doesn't just proceed work from being preachy, it also creates infinite in a piece of artwork, allowing room for artist and viewer alike to ask questions, like what the existent difference is between high and low culture, or betwixt conservative and radical, or whether the avant-garde'southward rage for the new was ever as original as they idea information technology was. (After all, Ezra Pound hailed the modernist movement with the phrase "make it new" decades before the sixties motility, and he supposedly lifted the phrase from a volume of Confucian philosophy.)

The desire to make something completely new is an old ane, contradictory by nature and nigh incommunicable to truly accomplish, yet artists keep to try, to the caste that this goal might be the main thread linking them to past generations of artists. It's almost similar they can't help themselves. Even Cooper, in his cocky-described advanced age, having written six books and countless reviews, has gone back to making avant-garde visual art; in 2015 he had a show of digital montages at Miami-Dade College Museum of Fine art and Design. He's kept at it, even though he acknowledges that "the cutting edge e'er becomes predictable after a while." So why bother pursuing it at all? "I like the thought that there's failure built into it," he explained. "That'south beautiful to me."

Mary Mann is the author of the forthcoming Yawn: Adventures in Boredom (FSG Originals). Her writing has as well appeared in The New York Times, Smithsonian, The Believer, and The Los Angeles Review of Books.

Source: https://www.musicandliterature.org/features/2016/11/21/words-aint-what-they-used-to-be-a-conversation-with-bernard-cooper

0 Response to "The Fine Art of Sighing by Bernard Cooper Full Text"

Postar um comentário